The Theme is Continuity American Foreign Policy Third World Cold War

Isolationism

Isolationism or non-interventionism was a tradition in America's foreign policy for its first two centuries.

Learning Objectives

Explain the historical reasons for American isolationism in foreign affairs

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- President George Washington established non-interventionism in his farewell address, and this policy was continued by Thomas Jefferson.

- The United States policy of non-intervention was maintained throughout most of the nineteenth century. The first significant foreign intervention by the United States was the Spanish-American War, which saw it occupy and control the Philippines.

- In the wake of the First World War, the non-interventionist tendencies of U.S. foreign policy were in full force. First, the United States Congress rejected President Woodrow Wilson's most cherished condition of the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations.

- The near total humiliation of Germany in the wake of World War I, laid the groundwork for a pride-hungry German people to embrace Adolf Hitler's rise to power. Non-intervention eventually contributed to Hitler's rise to power in the 1930s.

Key Terms

- non-interventionism: Non-interventionism, the diplomatic policy whereby a nation seeks to avoid alliances with other nations in order to avoid being drawn into wars not related to direct territorial self-defense, has had a long history in the United States.

- brainchild: A creation, original idea, or innovation, usually used to indicate the originators

- isolationism: The policy or doctrine of isolating one's country from the affairs of other nations by declining to enter into alliances, foreign economic commitments, foreign trade, international agreements, etc..

Background

For the first 200 years of United States history, the national policy was isolationism and non-interventionism. George Washington's farewell address is often cited as laying the foundation for a tradition of American non-interventionism: "The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities."

No Entangling Alliances in the Nineteenth Century

President Thomas Jefferson extended Washington's ideas in his March 4, 1801 inaugural address: "peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none. " Jefferson's phrase "entangling alliances" is, incidentally, sometimes incorrectly attributed to Washington.

Non-interventionism continued throughout the nineteeth century. After Tsar Alexander II put down the 1863 January Uprising in Poland, French Emperor Napoleon III asked the United States to "join in a protest to the Tsar. " Secretary of State William H Seward declined, "defending 'our policy of non-intervention — straight, absolute, and peculiar as it may seem to other nations,'" and insisted that "the American people must be content to recommend the cause of human progress by the wisdom with which they should exercise the powers of self-government, forbearing at all times, and in every way, from foreign alliances, intervention, and interference. "

The United States' policy of non-intervention was maintained throughout most of the nineteenth century. The first significant foreign intervention by the United States was the Spanish-American War, which saw the United States occupy and control the Philipines.

Twentieth Century Non-intervention

Theodore Roosevelt's administration is credited with inciting the Panamanian Revolt against Colombia in order to secure construction rights for the Panama Canal, begun in 1904. President Woodrow Wilson, after winning re-election with the slogan, "He kept us out of war," was nonetheless compelled to declare war on Germany and so involve the nation in World War I when the Zimmerman Telegram was discovered. Yet non-interventionist sentiment remained; the U.S. Congress refused to endorse the Treaty of Versailles or the League of Nations.

Non-Interventionism between the World Wars

In the wake of the First World War, the non-interventionist tendencies of U.S. foreign policy were in full force. First, the United States Congress rejected president Woodrow Wilson's most cherished condition of the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations. Many Americans felt that they did not need the rest of the world, and that they were fine making decisions concerning peace on their own. Even though "anti-League" was the policy of the nation, private citizens and lower diplomats either supported or observed the League of Nations. This quasi-isolationism shows that the United States was interested in foreign affairs but was afraid that by pledging full support for the League, it would lose the ability to act on foreign policy as it pleased.

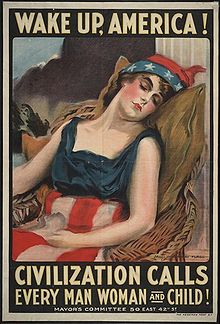

Wake Up America!: At the dawn of WWI, posters like this asked America to abandon its isolationist policies.

Although the United States was unwilling to commit to the League of Nations, they were willing to engage in foreign affairs on their own terms. In August 1928, 15 nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, brainchild of American Secretary of State Frank Kellogg and French Foreign Minister Aristride Briand. This pact that was said to have outlawed war and showed the United States commitment to international peace had its semantic flaws. For example, it did not hold the United States to the conditions of any existing treaties, it still allowed European nations the right to self-defense, and stated that if one nation broke the pact, it would be up to the other signatories to enforce it. The Kellogg-Briand Pact was more of a sign of good intentions on the part of the United States, rather than a legitimate step towards the sustenance of world peace.

Non-interventionism took a new turn after the Crash of 1929. With the economic hysteria, the United States began to focus solely on fixing its economy within its borders and ignored the outside world. As the world's democratic powers were busy fixing their economies within their borders, the fascist powers of Europe and Asia moved their armies into a position to start World War II. With military victory came the spoils of war –a very draconian pummeling of Germany into submission, via the Treaty of Versailles. This near-total humiliation of Germany in the wake of World War I, as the treaty placed sole blame for the war on the nation, laid the groundwork for a pride-hungry German people to embrace Adolf Hitler's rise to power.

World War I and the League of Nations

The League of Nations was created as an international organization after WWI.

Learning Objectives

Explain the historical rise and fall of the League of Nations after World War I

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The League of Nations was suggested in Wilson's 14 points.

- The League of Nations' functions included arbitration and peace-keeping. However, it did not have an army to enforce power.

- The League of Nations was the precursor to the United Nations.

Key Terms

- arbitration: A process through which two or more parties use an arbitrator or arbiter (an impartial third party) in order to resolve a dispute.

- World Trade Organization: an international organization designed by its founders to supervise and liberalize international trade

- disarmament: The reduction or the abolition of the military forces and armaments of a nation, and of its capability to wage war

- intergovernmental: Of, pertaining to, or involving two or more governments

An Early Attempt at International Organization

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Talks that ended the First World War. The form and ideals were drawn to some extent from US President Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points. The League was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. Its primary goals, as stated in its Covenant, included preventing wars through collective security and disarmament, and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration. Other issues in this and related treaties included labor conditions, just treatment of native inhabitants, human and drug trafficking, arms trade, global health, prisoners of war, and protection of minorities in Europe. At the height of its development, from 28 September 1934 to 23 February 1935, it had 58 member nations.

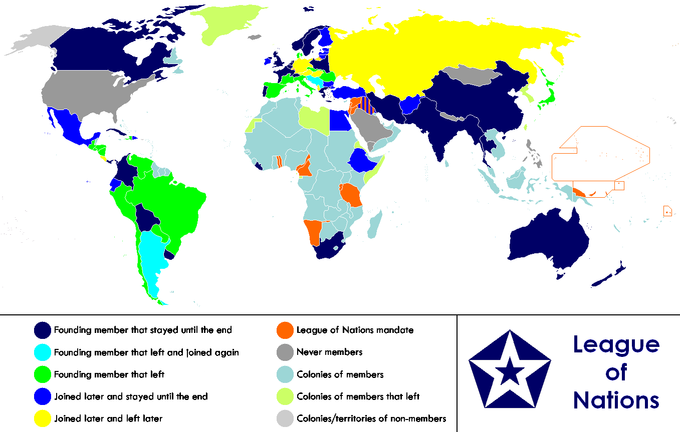

Map of League of Nations: The countries on the map represent those that have been involved with the League of Nations.

A Lack of Leverage

The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift from the preceding hundred years. The League lacked its own armed force, and depended on the Great powers to enforce its resolutions, keep to its economic sanctions, or provide an army when needed. However, the Great Powers were often reluctant to do so. Sanctions could hurt League members, so they were reluctant to comply with them.

Failure of the League

After a number of notable successes and some early failures in the 1920s, the League ultimately proved incapable of preventing aggression by the Axis powers. In the 1930s, Germany withdrew from the League, as did Japan, Italy, Spain, and others. The onset of World War II showed that the League had failed its primary purpose, which was to prevent any future world war. The United Nations (UN) replaced it after the end of the war and inherited a number of agencies and organizations founded by the League.

World War II

Although isolationists kept the U.S. out of WWII for years, the interventionists eventually had their way and the U.S. declared war in 1941.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast the arguments made by interventionists and non-interventionists with respect to American involvement in World War II

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Fascism was becoming a growing fear in the United States, and after Germany invaded Poland, many wondered if the US should intervene.

- Many famous public figures called for isolationism, such as professors and even Charles Lindburg.

- The Lend Lease program was a way to ease into interventionism, though the US stayed out militarily.

Key Terms

- Neutrality Act: The Neutrality Acts were passed by the United State Congress in the 1930's and sought to ensure that the US would not become entangled again in foreign conflicts.

As Europe moved closer and closer to war in the late 1930s, the United States Congress was doing everything it could to prevent it. Between 1936 and 1937, much to the dismay of the pro-British President Roosevelt, Congress passed the Neutrality Acts. In the final Neutrality Act, Americans could not sail on ships flying the flag of a belligerent nation or trade arms with warring nations, potential causes for U.S. entry into war.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, and Britain and France subsequently declared war on Germany, marking the start of World War II. In an address to the American people two days later, President Roosevelt assured the nation that he would do all he could to keep them out of war. However, he also said: "When peace has been broken anywhere, the peace of all countries everywhere is in danger. "

Germany invades Poland: Germany invading Poland caused the United States to reconsider intervening.

The war in Europe split the American people into two distinct groups: non-interventionists and interventionists. The basic principle of the interventionist argument was fear of German invasion. By the summer of 1940, France had fallen to the Germans, and Britain was the only democratic stronghold between Germany and the United States. Interventionists were afraid of a world after this war, a world where they would have to coexist with the fascist power of Europe. In a 1940 speech, Roosevelt argued, "Some, indeed, still hold to the now somewhat obvious delusion that we … can safely permit the United States to become a lone island … in a world dominated by the philosophy of force. " A national survey found that in the summer of 1940, 67% of Americans believed that a German-Italian victory would endanger the United States, that if such an event occurred 88% supported "arm[ing] to the teeth at any expense to be prepared for any trouble", and that 71% favored "the immediate adoption of compulsory military training for all young men."

Ultimately, the rift between the ideals of the United States and the goals of the fascist powers is what was at the core of the interventionist argument. "How could we sit back as spectators of a war against ourselves? " writer Archibald MacLeish questioned. The reason why interventionists said we could not coexist with the fascist powers was not due to economic pressures or deficiencies in our armed forces, but rather because it was the goal of fascist leaders to destroy the American ideology of democracy. In an address to the American people on December 29, 1940, President Roosevelt said, "…the Axis not merely admits but proclaims that there can be no ultimate peace between their philosophy of government and our philosophy of government."

However, there were still many who held on to the age-old tenets of non-interventionism. Although a minority, they were well organized, and had a powerful presence in Congress. Non-interventionists rooted a significant portion of their arguments in historical precedent, citing events such as Washington's farewell address and the failure of World War I. In 1941, the actions of the Roosevelt administration made it clearer and clearer that the United States was on its way to war. This policy shift, driven by the President, came in two phases. The first came in 1939 with the passage of the Fourth Neutrality Act, which permitted the United States to trade arms with belligerent nations, as long as these nations came to America to retrieve the arms and paid for them in cash. This policy was quickly dubbed "Cash and Carry. " The second phase was the Lend-Lease Act of early 1941. This act allowed the President "to lend, lease, sell, or barter arms, ammunition, food, or any 'defense article' or any 'defense information' to 'the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.' He used these two programs to side economically with the British and the French in their fight against the Nazis.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack was intended as a preventive action in order to keep the U.S. Pacific Fleet from interfering with military actions the Empire of Japan was planning in Southeast Asia against overseas territories of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the United States. The following day, the United States declared war on Japan. Domestic support for non-interventionism disappeared. Clandestine support of Britain was replaced by active alliance. Subsequent operations by the U.S. prompted Germany and Italy to declare war on the U.S. on December 11, which was reciprocated by the U.S. the same day.

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted atomic bombings of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. These two events represent the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.

Interventionism

After WWII, the US's foreign policy was characterized by interventionism, which meant the US was directly involved in other states' affairs.

Learning Objectives

Define interventionism and its relation to American foreign policy

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In the period between World War I and World War II, the US's foreign policy was characterized by isolationism, which meant it preferred to be isolated from the affairs of other countries.

- The ideological goals of the fascist powers in Europe during World War II and the growing aggression of Germany led many Americans to fear for the security of their nation, and thus call for an end to the US policy of isolationism.

- In the early 1940s, US policies such as the Cash and Carry Program and the Lend-Lease Act provided assistance to the Allied Powers in their fight against Germany. This growing involvement by the US marked a move away from isolationist tendencies towards interventionism.

- After World War II, the US became fully interventionist. US interventionism was motivated primarily by the goal of containing the influence of communism, and essentially meant the US was now a leader in global security, economic, and social issues.

Key Terms

- isolationism: The policy or doctrine of isolating one's country from the affairs of other nations by declining to enter into alliances, foreign economic commitments, foreign trade, international agreements, etc..

- interventionism: The political practice of intervening in a sovereign state's affairs.

Abandoning Isolationism

As the world was quickly drawn into WWII, the United States ' isolationist policies were replaced by more interventionism. In part, this foreign policy shift sprung from Euro-American relations and public fear.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland; Britain and France subsequently declared war on Germany, marking the start of World War II. In an address to the American People two days later, President Roosevelt assured the nation that he would do all he could to keep them out of war. However, even though he was intent on neutrality as the official policy of the United States, he still echoed the dangers of staying out of this war. He also cautioned the American people to not let their wish to avoid war at all costs supersede the security of the nation.

The war in Europe split the American people into two distinct groups: non-interventionists and interventionists. The two sides argued over America's involvement in this Second World War. The basic principle of the interventionist argument was fear of German invasion. By the summer of 1940, France had fallen to the Germans, and Britain was the only democratic stronghold between Germany and the United States. Interventionists feared that if Britain fell, their security as a nation would shrink immediately. A national survey found that in the summer of 1940, 67% of Americans believed that a German-Italian victory would endanger the United States, that if such an event occurred 88% supported "arm[ing] to the teeth at any expense to be prepared for any trouble", and that 71% favored "the immediate adoption of compulsory military training for all young men".

Ultimately, the ideological rift between the ideals of the United States and the goals of the fascist powers is what made the core of the interventionist argument.

Moving Towards War

As 1940 became 1941, the actions of the Roosevelt administration made it more and more clear that the United States was on a course to war. This policy shift, driven by the President, came in two phases. The first came in 1939 with the passage of the Fourth Neutrality Act, which permitted the United States to trade arms with belligerent nations, as long as these nations came to America to retrieve the arms, and pay for them in cash. This policy was quickly dubbed 'Cash and Carry.' The second phase was the Lend-Lease Act of early 1941. This act allowed the President "to lend, lease, sell, or barter arms, ammunition, food, or any 'defense article' or any 'defense information' to 'the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.' He used these two programs to side economically with the British and the French in their fight against the Nazis.

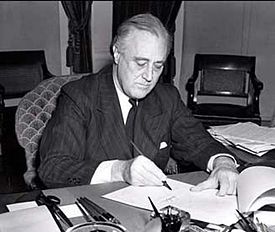

President Roosevelt signing the Lend-Lease Act: The Lend Lease Act allowed the United States to tip-toe from isolationism while still remaining militarily neutral.

Policies of Interventionism

After WWII, the United States took a policy of interventionism in order to contain communist influence abroad. Such forms of interventionism included giving aid to European nations to rebuild, having an active role in the UN, NATO, and police actions around the world, and involving the CIA in several coup take overs in Latin America and the Middle East. The US was not merely non-isolationist (i.e. the US was not merely abandoning policies of isolationism), but actively intervening and leading world affairs.

Marshall Plan and US Interventionism: After WWII, the US's foreign policy was characterized by interventionism. For example, immediately after the end of the war, the US supplied Europe with monetary aid in hopes of combating the influence of communism in a vulnerable, war-weakened Europe. This label was posted on Marshall Aid packages.

The Cold War and Containment

Truman's Containment policy was the first major policy during the Cold War and used numerous strategies to prevent the spread of communism abroad.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the doctrine of Containment and its role during the Cold War

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Containment was suggested by diplomat George Kennan who eagerly suggested the United States stifle communist influence in Eastern Europe and Asia.

- One of the ways to accomplish this was by establishing NATO so the Western European nations had a defense against communist influence.

- After Vietnam and détente, President Jimmy Carter focused less on containment and more on fighting the Cold War by promoting human rights in hot spot countries.

Key Terms

- deterrence: Action taken by states or alliances of nations against equally powerful alliances to prevent hostile action

- rollback: A withdrawal of military forces.

The Cold War and Containment

Containment was a United States policy using numerous strategies to prevent the spread of communism abroad. A component of the Cold War, this policy was a response to a series of moves by the Soviet Union to enlarge its communist sphere of influence in Eastern Europe, China, Korea, and Vietnam. It represented a middle-ground position between détente and rollback.

The basis of the doctrine was articulated in a 1946 cable by United States diplomat, George F. Kennan. As a description of United States foreign policy, the word originated in a report Kennan submitted to the U.S. defense secretary in 1947—a report that was later used in a magazine article.

The word containment is associated most strongly with the policies of United States President Harry Truman (1945–53), including the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a mutual defense pact. Although President Dwight Eisenhower (1953–61) toyed with the rival doctrine of rollback, he refused to intervene in the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. President Lyndon Johnson (1963–69) cited containment as a justification for his policies in Vietnam. President Richard Nixon (1969–74), working with his top advisor Henry Kissinger, rejected containment in favor of friendly relations with the Soviet Union and China; this détente, or relaxation of tensions, involved expanded trade and cultural contacts.

President Jimmy Carter (1976–81) emphasized human rights rather than anti-communism, but dropped détente and returned to containment when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979. President Ronald Reagan (1981–89), denouncing the Soviet state as an "evil empire", escalated the Cold War and promoted rollback in Nicaragua and Afghanistan. Central programs begun under containment, including NATO and nuclear deterrence, remained in effect even after the end of the war.The word containment is associated most strongly with the policies of United States President Harry Truman (1945–53), including the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a mutual defense pact. Although President Dwight Eisenhower (1953–61) toyed with the rival doctrine of rollback, he refused to intervene in the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. President Lyndon Johnson (1963–69) cited containment as a justification for his policies in Vietnam. President Richard Nixon (1969–74), working with his top advisor Henry Kissinger, rejected containment in favor of friendly relations with the Soviet Union and China; this détente, or relaxation of tensions, involved expanded trade and cultural contacts.

Détente and Human Rights

Détente was a period in U.S./Soviet relations in which tension between the two superpowers was eased.

Learning Objectives

Explain the significance of the Helsinki Accords for the history of human rights in the 20th century and define the doctrine of Détente and its use by the United States during the Cold War

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Détente was an effort by the super powers to ease tensions in the Cold War.

- The Nixon and Brezhnev administrations led the way with détente, talking about world issues and signing treaties such as SALT I and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

- The Carter administration ushered in a human rights component to détente, criticizing the USSR's poor record of human rights. The USSR countered by criticizing the US for its own human rights record, and for interfering in USSR domestic affairs.

- During the Carter administration, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe created the Helsinki Accords, which addressed human rights in the USSR.

- Détente ended in 1980 with Soviet interference in Afghanistan, the US boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, and Reagan's election.

Key Terms

- Warsaw Pact: A pact (long-term alliance treaty) signed on May 14, 1955 by the Soviet Union and its Communist military allies in Europe.

- Détente: French for "relaxation," détente is the easing of tense relations, particularly in a political situation. The term is often used in reference to the general easing of geo-political tensions between the Soviet Union and the US, which began in 1971 and ended in 1980.

- Helsinki Accords: A declaration in an attempt to improve relations between the Communist bloc and the West. Developed in Europe, the Helsinki Accords called for human rights improvements in the USSR.

Détente

Détente, French for "relaxation", is an international theory that refers to the easing of strained relations, especially in a political situation. The term is often used in reference to the general easing of relations between the Soviet Union and the United States in 1971, a thawing at a period roughly in the middle of the Cold War.

Treaties Toward Peace

The most important treaties of détente were developed when the Nixon Administration came into office in 1969. The Political Consultative Committee of the Warsaw Pact sent an offer to the West, urging to hold a summit on "security and cooperation in Europe". The West agreed and talks began towards actual limits to the nuclear capabilities of the two superpowers. This ultimately led to the signing of the treaty in 1972. This treaty limited each power's nuclear arsenals, though it was quickly rendered out-of-date as a result of the development of a new type of warhead. In the same year that SALT I was signed, the Biological Weapons Convention and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty were also concluded.

A follow up treaty, SALT II was discussed but was never ratified by the United States. There is debate among historians as to how successful the détente period was in achieving peace. The two superpowers agreed to install a direct hotline between Washington DC and Moscow, the so-called "red telephone," enabling both countries to quickly interact with each other in a time of urgency. The SALT II pact of the late 1970s built on the work of the SALT I talks, ensuring further reduction in arms by the Soviets and by the US.

Nixon and Brezhnev: President Nixon and Premier Brezhnev lead in the high period of détente, signing treaties such as SALT I and the Helsinki Accords.

The Helsinki Accords and Human Rights in the USSR

The Helsinki Accords, in which the Soviets promised to grant free elections in Europe, has been seen as a major concession to ensure peace by the Soviets. The Helsinki Accord were developed by the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, a wide ranging series of agreements on economic, political, and human rights issues. The CSCE was initiated by the USSR, involving 35 states throughout Europe.

Among other issues, one of the most prevalent and discussed after the conference was the human rights violations in the Soviet Union. The Soviet Constitution directly violated the declaration of Human Rights from the United Nations, and this issue became a prominent point of dissonance between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Because the Carter administration had been supporting human rights groups inside the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev accused the administration of interference in other countries' internal affairs. This prompted intense discussion of whether or not other nations may interfere if basic human rights are being violated, such as freedom of speech and religion. The basic differences between the philosophies of a democracy and a single-party state did not allow for reconciliation of this issue. Furthermore, the Soviet Union proceeded to defend their internal policies on human rights by attacking American support of countries like South Africa and Chile, which were known to violate many of the same human rights issues.

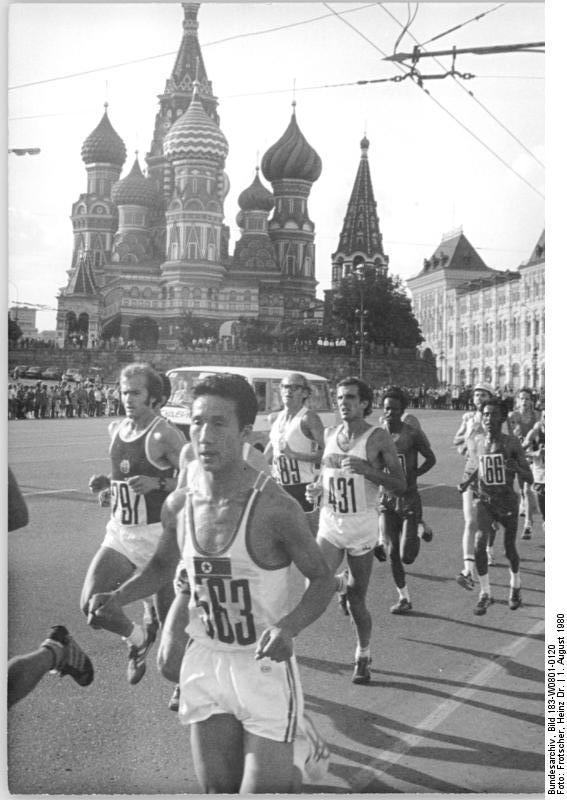

Détente ended after the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, which led to America's boycott in the 1980s Olympics in Moscow. Ronald Reagan's election in 1980, based on an anti-détente campaign, marked the close of détente and a return to Cold War tension.

1980 Moscow Olympics: After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, many countries boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games, held in Moscow. This photograph depicts Olympic runners in the 1980 games in front of Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow.

Foreign Policy After the Cold War

The post-Cold War era saw optimism, and the balance of power shifted solely to the United States.

Learning Objectives

Explain the origins and elements of the New World Order after the end of the Cold War

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The post-Cold War era saw the United States as the sole leader of the world affairs.

- The Cold War set the standard for military-industrial complexes which, while weaker than during the Cold War, is a legacy that continues to exist.

- The new world order as theorized between Bush and Gorbachev saw optimism and democratization for countries.

Key Terms

- War on Terror: The war on terror is a term commonly applied to an international military campaign begun by the United States and the United Kingdom with support from other countries after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

- new world order: The term new world order has been used to refer to any new period of history evidencing a dramatic change in world political thought and the balance of power. Despite various interpretations of this term, it is primarily associated with the ideological notion of global governance only in the sense of new collective efforts to identify, understand, or address worldwide problems that go beyond the capacity of individual nation-states to solve. The most widely discussed application of the phrase in recent times came at the end of the Cold War.

- military-industrial complex: The armed forces of a nation together with the industries that supply their weapons and materiel.

Post-Cold War Foreign Policy

Introduction

With the breakup of the Soviet Union into separate nations, and the re-emergence of the nation of Russia, the world of pro-U.S. and pro-Soviet alliances broke down. Different challenges presented themselves, such as climate change and the threat of nuclear terrorism. Regional powerbrokers in Iraq and Saddam Hussein challenged the peace with a surprise attack on the small nation of Kuwait in 1991.

President George H.W. Bush organized a coalition of allied and Middle Eastern powers that successfully pushed back the invading forces, but stopped short of invading Iraq and capturing Hussein. As a result, the dictator was free to cause mischief for another twelve years. After the Gulf War, many scholars like Zbigniew Brzezinski claimed that the lack of a new strategic vision for U.S. foreign policy resulted in many missed opportunities for its foreign policy. The United States mostly scaled back its foreign policy budget as well as its cold war defense budget during the 1990s, which amounted to 6.5% of GDP while focusing on domestic economic prosperity under President Clinton, who succeeded in achieving a budget surplus for 1999 and 2000.

The aftermath of the Cold War continues to influence world affairs. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the post–Cold War world was widely considered as unipolar, with the United States the sole remaining superpower. The Cold War defined the political role of the United States in the post–World War II world: by 1989 the U.S. held military alliances with 50 countries, and had 526,000 troops posted abroad in dozens of countries, with 326,000 in Europe (two-thirds of which in west Germany) and about 130,000 in Asia (mainly Japan and South Korea). The Cold War also marked the apex of peacetime military-industrial complexes, especially in the United States, and large-scale military funding of science. These complexes, though their origins may be found as early as the 19th century, have grown considerably during the Cold War. The military-industrial complexes have great impact on their countries and help shape their society, policy and foreign relations.

New World Order

A concept that defined the world power after the Cold-War was known as the new world order. The most widely discussed application of the phrase of recent times came at the end of the Cold War. Presidents Mikhail Gorbachev and George H.W. Bush used the term to try to define the nature of the post Cold War era, and the spirit of a great power cooperation they hoped might materialize. Historians will look back and say this was no ordinary time but a defining moment: an unprecedented period of global change, and a time when one chapter ended and another began.

Bush and Gorbachev: Bush and Gorbachev helped shape international relation theories after the cold war.

War on Terrorism

A concept that defined the world power after the Cold-War was known as the new world order. The most widely discussed application of the phrase of recent times came at the end of the Cold War. Presidents Mikhail Gorbachev and George H.W. Bush used the term to try to define the nature of the post Cold War era, and the spirit of a great power cooperation they hoped might materialize. Historians will look back and say this was no ordinary time but a defining moment: an unprecedented period of global change, and a time when one chapter ended and another began.

Furthermore, when no weapons of mass destruction were found after a military conquest of Iraq, there was worldwide skepticism that the war had been fought to prevent terrorism, and the continuing war in Iraq has had serious negative public relations consequences for the image of the United States.

Multipolar World

The big change during these years was a transition from a bipolar world to a multipolar world. While the United States remains a strong power economically and militarily, rising nations such as China, India, Brazil, and Russia as well as a united Europe have challenged its dominance. Foreign policy analysts such as Nina Harchigian suggest that the six emerging big powers share common concerns: free trade, economic growth, prevention of terrorism, and efforts to stymie nuclear proliferation. And if they can avoid war, the coming decades can be peaceful and productive provided there are no misunderstandings or dangerous rivalries.

The War on Terrorism

The War on Terror refers to an international military campaign begun by the U.S. and the U.K. after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Learning Objectives

Identify the main elements of U.S. foreign policy during the War on Terror

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The campaign 's official purpose was to eliminate al-Qaeda and other militant organizations, and the two main military operations associated with the War on Terror were Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq.

- The Bush administration and the Western media used the term to denote a global military, political, legal and ideological struggle targeting both organizations designated as terrorist and regimes accused of supporting them.

- On 20 September 2001, in the wake of the 11 September attacks, George W. Bush delivered an ultimatum to the Taliban government of Afghanistan to turn over Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda leaders operating in the country or face attack.

- In October 2002, a large bipartisan majority in the United States Congress authorized the president to use force if necessary to disarm Iraq in order to "prosecute the war on terrorism. " The Iraq War began in March 2003 with an air campaign, which was immediately followed by a U.S. ground invasion.

Key Terms

- Islamist: A person who espouses Islamic fundamentalist beliefs.

- War on Terror: The war on terror is a term commonly applied to an international military campaign begun by the United States and the United Kingdom with support from other countries after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

- terrorism: The deliberate commission of an act of violence to create an emotional response through the suffering of the victims in the furtherance of a political or social agenda.

Introduction

The War on Terror is a term commonly applied to an international military campaign begun by the United States and United Kingdom with support from other countries after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The campaign's official purpose was to eliminate al-Qaeda and other militant organizations. The two main military operations associated with the War on Terror were Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq.

9/11 Attacks on the World Trade Center: The north face of Two World Trade Center (south tower) immediately after being struck by United Airlines Flight 175.

The phrase "War on Terror" was first used by U.S. President George W. Bush on 20 September 2001. The Bush administration and the Western media have since used the term to denote a global military, political, legal, and ideological struggle targeting organizations designated as terrorist and regimes accused of supporting them. It was typically used with a particular focus on Al-Qaeda and other militant Islamists. Although the term is not officially used by the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama, it is still commonly used by politicians, in the media, and officially by some aspects of government, such as the United States' Global War on Terrorism Service Medal.

Precursor to 9/11 Attacks

The origins of al-Qaeda as a network inspiring terrorism around the world and training operatives can be traced to the Soviet war in Afghanistan (December 1979–February 1989). The United States supported the Islamist mujahadeen guerillas against the military forces of the Soviet Union and the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. In May 1996 the group World Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders (WIFJAJC), sponsored by Osama bin Laden and later reformed as al-Qaeda, started forming a large base of operations in Afghanistan, where the Islamist extremist regime of the Taliban had seized power that same year. In February 1998, Osama bin Laden, as the head of al-Qaeda, signed a fatwā declaring war on the West and Israel, and later in May of that same year al-Qaeda released a video declaring war on the U.S. and the West.

U.S. Military Responses (Afghanistan)

On 20 September 2001, in the wake of the 11 September attacks, George W. Bush delivered an ultimatum to the Taliban government of Afghanistan to turn over Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda leaders operating in the country or face attack. The Taliban demanded evidence of bin Laden's link to the 11 September attacks and, if such evidence warranted a trial, they offered to handle such a trial in an Islamic Court. The US refused to provide any evidence.

Subsequently, in October 2001, US forces invaded Afghanistan to oust the Taliban regime. On 7 October 2001, the official invasion began with British and U.S. forces conducting airstrike campaigns over enemy targets. Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan, fell by mid-November. The remaining al-Qaeda and Taliban remnants fell back to the rugged mountains of eastern Afghanistan, mainly Tora Bora. In December, Coalition forces (the U.S. and its allies) fought within that region. It is believed that Osama bin Laden escaped into Pakistan during the battle.

U.S. Military Responses (Iraq)

Iraq had been listed as a State Sponsor of Terrorism by the U.S. since 1990, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Iraq was also on the list from 1979 to 1982; it had been removed so that the U.S. could provide material support to Iraq in its war with Iran. Hussein's regime proved a continuing problem for the U.N. and Iraq's neighbors due to its use of chemical weapons against Iranians and Kurds.

In October 2002, a large bipartisan majority in the United States Congress authorized the president to use force if necessary to disarm Iraq in order to "prosecute the war on terrorism. " After failing to overcome opposition from France, Russia, and China against a UNSC resolution that would sanction the use of force against Iraq, and before the U.N. weapons inspectors had completed their inspections, the U.S. assembled a "Coalition of the Willing" composed of nations who pledged support for its policy of regime change in Iraq.

The Iraq War began in March 2003 with an air campaign, which was immediately followed by a U.S.-led ground invasion. The Bush administration stated that the invasion was the "serious consequences" spoken of in the UNSC Resolution 1441. The Bush administration also stated that the Iraq War was part of the War on Terror, a claim that was later questioned.

Baghdad, Iraq's capital city, fell in April 2003 and Saddam Hussein's government quickly dissolved. On 1 May 2003, Bush announced that major combat operations in Iraq had ended. However, an insurgency arose against the U.S.-led coalition and the newly developing Iraqi military and post-Saddam government. The insurgency, which included al-Qaeda affiliated groups, led to far more coalition casualties than the invasion. Iraq's former president, Saddam Hussein, was captured by U.S. forces in December 2003. He was executed in 2006.

Licenses and Attributions

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- United States non-interventionism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- non-interventionism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- isolationism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- brainchild. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- League of Nations. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- arbitration. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- disarmament. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- intergovernmental. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- World Trade Organization. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- World War II. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- United States non-interventionism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Attack on Pearl Harbor. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Neutrality Acts of 1930s. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Neutrality Act. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- United States non-interventionism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- interventionism. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- isolationism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Containment. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- rollback. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- deterrence. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Head and shoulders portrait of a balding man, wearing a suit and tie.. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Du00e9tente. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Helsinki Accords. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Detente. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Warsaw Pact. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo.svg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Head and shoulders portrait of a balding man, wearing a suit and tie.. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bundesarchiv Bild 183-W0801-0120, Moskau, XXII.nOlympiade, Marathon, Cierpinski, Chun Son Kon,. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- United States non-interventionism. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- War on Terror. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- new world order. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- military-industrial complex. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Head and shoulders portrait of a balding man, wearing a suit and tie.. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bundesarchiv Bild 183-W0801-0120, Moskau, XXII.nOlympiade, Marathon, Cierpinski, Chun Son Kon,. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcT9LqnvSsah6yXeFN5hutmqciII5jj1MFVN1Cru4Y4vGz7BBT8. License: CC BY: Attribution

- War on Terror. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_on_Terror. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- War on Terror. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- terrorism. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Islamist. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/FlaggWakeUpAmerica.jpg/220px-FlaggWakeUpAmerica.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US-MarshallPlanAid-Logo. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Head and shoulders portrait of a balding man, wearing a suit and tie.. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bundesarchiv Bild 183-W0801-0120, Moskau, XXII.nOlympiade, Marathon, Cierpinski, Chun Son Kon,. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Provided by: https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcT9LqnvSsah6yXeFN5hutmqciII5jj1MFVN1Cru4Y4vGz7BBT8. License: CC BY: Attribution

- September 11 attacks. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/September_11_attacks. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Source: https://www.coursehero.com/study-guides/boundless-politicalscience/the-history-of-american-foreign-policy/